Devangshu Dutta

January 10, 2017

In this piece I’ll just focus on one aspect of technology – artificial intelligence or AI – that is likely to shape many aspects of the retail business and the consumer’s experience over the coming years.

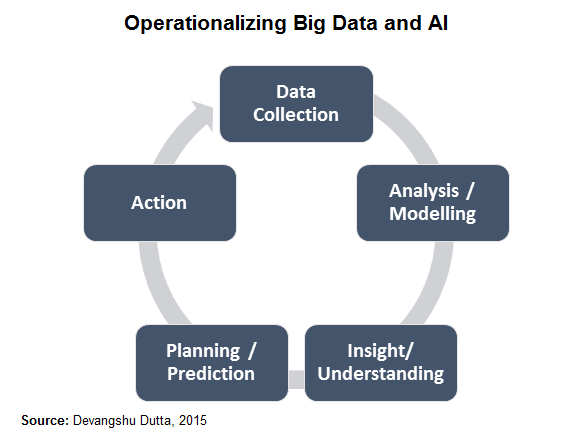

To be able to see the scope of its potential all-pervasive impact we need to go beyond our expectations of humanoid robots. We also need to understand that artificial intelligence works on a cycle of several mutually supportive elements that enable learning and adaptation. The terms “big data” and “analytics” have been bandied about a lot, but have had limited impact so far in the retail business because it usually only touches the first two, at most three, of the necessary elements.

“Big data” models still depend on individuals in the business taking decisions and acting based on what is recommended or suggested by the analytics outputs, and these tend to be weak links which break the learning-adaptation chain. Of course, each of these elements can also have AI built in, for refinement over time.

Certainly retailers with a digital (web or mobile) presence are in a better position to use and benefit from AI, but that is no excuse for others to “roll over and die”. I’ll list just a few aspects of the business already being impacted and others that are likely to be in the future.

On the consumer-side, AI can deliver a far higher degree of personalisation of the experience than has been feasible in the last few decades. While I’ve described different aspects, now see them as layers one built on the other, and imagine the shopping experience you might have as a consumer. If the scenario seems as if it might be from a sci-fi movie, just give it a few years. After all, moving staircases and remote viewing were also fantasy once.

On the business end it potentially offers both flexibility and efficiency, rather than one at the cost of the other. But we’ll have to tackle that area in a separate piece.

(Also published in the Business Standard.)

Devangshu Dutta

January 21, 2016

Aggregator models and hyperlocal delivery, in theory, have some significant advantages over existing business models.

Unlike an inventory-based model, aggregation is asset-light, allowing rapid building of critical mass. A start-up can tap into existing infrastructure, as a bridge between existing retailers and the consumer. By tapping into fleeting consumption opportunities, the aggregator can actually drive new demand to the retailer in the short term.

A hyperlocal delivery business can concentrate on understanding the nuances of a customer group in a small geographic area and spend its management and financial resources to develop a viable presence more intensively.

However, both business models are typically constrained for margins, especially in categories such as food and grocery. As volume builds up, it’s feasible for the aggregator to transition at least part if not the entire business to an inventory-based model for improved fulfilment and better margins. By doing so the aggregator would, therefore, transition itself to being the retailer.

Customer acquisition has become very expensive over the last couple of years, with marketplaces and online retailers having driven up advertising costs – on top of that, customer stickiness is very low, which means that the platform has to spend similar amounts of money to re-acquire a large chunk of customers for each transaction.

The aggregator model also needs intensive recruitment of supply-side relationships. A key metric for an aggregator’s success is the number of local merchants it can mobilise quickly. After the initial intensive recruitment the merchants need to be equipped to use the platform optimally and also need to be able to handle the demand generated.

Most importantly, the acquisitions on both sides – merchants and customers – need to move in step as they are mutually-reinforcing. If done well, this can provide a higher stickiness with the consumer, which is a significant success outcome.

For all the attention paid to the entry and expansion of multinational retailers and nationwide ecommerce growth, retail remains predominantly a local activity. The differences among customers based on where they live or are located currently and the immediacy of their needs continue to drive diversity of shopping habits and the unpredictability of demand. Services and information based products may be delivered remotely, but with physical products local retailers do still have a better chance of servicing the consumer.

What has been missing on the part of local vendors is the ability to use web technologies to provide access to their customers at a time and in a way that is convenient for the customers. Also, importantly, their visibility and the ability to attract customer footfall has been negatively affected by ecommerce in the last 2 years. With penetration of mobile internet across a variety of income segments, conditions are today far more conducive for highly localised and aggregation-oriented services. So a hyperlocal platform that focusses on creating better visibility for small businesses, and connecting them with customers who have a need for their products and services, is an opportunity that is begging to be addressed.

It is likely that each locality will end up having two strong players: a market leader and a follower. For a hyperlocal to fit into either role, it is critical to rapidly create viability in each location it targets, and – in order to build overall scale and continued attractiveness for investors – quickly move on to replicate the model in another location, and then another. They can become potential acquisition targets for larger ecommerce companies, which could acquire to not only take out potential competition but also to imbibe the learnings and capabilities needed to deal with demand microcosms.

High stake bets are being placed on this table – and some being lost with business closures – but the game is far from being played out yet.

admin

May 17, 2013

Organised by the Retailers Association of India the Delhi Retail Summit this year (10 May 2013) focussed on multi-fold growth for retailers utilising multiple channels to the consumer, with panel discussions and presentations by industry leaders who shared their experiences in exploiting the opportunities and dealing with the strategic and operational challenges of their varied businesses. Some snippets from the first panel discussion, comprising of the following panelists:

1. Devangshu Dutta, Chief Executive, Third Eyesight (Session Moderator)

2. Atul Ahuja, Vice President – Retail, Apollo Pharmacy

3. Lalit Agarwal, CMD, V-Mart Retail Ltd.

4. Atul Chand, Chief Executive, ITC Lifestyle

5. Rahul Chadha, Executive Director & CEO, Religare Wellness Ltd.

Devangshu Dutta

September 4, 2010

The last three years have been a roller coaster ride for food & grocery modern retail in India.

Progressive Grocer’s India edition was launched in September 2007, during what was an excellent series of years for the modern retail trade in the country.

It was a year after the launch of Reliance Fresh, and a few months after the acquisition of Trinethra’s chain of 170 stores by the traditionally conservative Aditya Birla Group. Spencer’s announced its plans to raise capital for expansion, while Food Bazaar together with its value-format non-food twin Big Bazaar already accounted for more than half the Future Group’s sales.

Other than the established corporate groups, new entrants such as Wadhawan were also well into growth through mergers and acquisitions, including their purchase of Sangam, Hindustan Unilever’s experiment at retailing directly to consumers, Sabka Bazaar and The Home Store.

The four largest foreign retailers were also making their presence felt through Walmart’s announcement of a joint-venture with Bharti in August, Tesco’s and Carrefour’s intensive investigations of the market and negotiations with potential partners, and Metro’s announcement of its planned growth to 100 outlets.

The modern retail engine seemed to be chugging along strongly. But there were also spots of trouble in paradise.

Protests against the opening of corporate chain stores were seen in a few states. In some cases state administrations even formally stepped in to ask for closure of corporate chains to avoid civic trouble, and it looked as if the lights were going out even before the party had really started!

Along with the battle between modern and traditional, both sides of the debate on foreign direct investment (FDI) into the Indian retail sector were also ramping up their arguments. There was vocal opposition from emerging large Indian retailers, as well as the small traders group, while investors and some of the prominent retailers championed the cause of foreign investment.

In both debates, international examples of the damage wrought by large or foreign retailers to local economies were quoted by those opposed to corporate retailers. And in both, the developmental aspects of modern retail were quoted by proponents of modern retail and FDI.

At Third Eyesight, in early 2007 we had carried out a study (“From Ripples to Waves”) on the increasing impact of modern retail on the supply chain. Amongst the study’s respondents, both retailers and suppliers had favourable things to say about the growth of modern retail and its impact on the supply chains for various products. There was not just talk of efficiency with fewer layers of transactions and lower costs, but also of effectiveness, with suppliers reporting 10-25% higher per square foot sales in modern retail stores as compared to their displays in traditional independent stores.

After years of resisting the impending changes to their ordering and servicing structures, major Indian FMCG and food brands became busy setting up or strengthening teams focussed on the modern trade or ‘organised’ corporate customers.

The market was rich with format experimentation for food and general merchandise retail, typically between 1,000 sq ft and 10,000 sq ft, but also with a gradual growing emphasis on 20,000-80,000 sq ft supermarkets and hypermarkets.

Literally hundreds of food brands from other countries actively sought to tap into the growing Indian market, and modern retailers offered them a familiar environment and a well-managed platform for launch.

At the same time, plenty of respondents also said that they had not made any significant changes to their business. Either inertia or fear of channel conflict was preventing them from pushing ahead with newer business models.

In short, there was no dearth of action and contradiction, no matter where you looked.

However, towards the end of 2007 and beginning of 2008, we had a sense of foreboding. With the rush to expand the store network to get first to some yet-invisible finish line, both property acquisition and human resource costs were driven up by a feeling of a shortage in both. I recall writing a column around that time, urging retailers to look at store productivity as their first priority (See: Priority #1: Store Productivity, Same Store Growth).

By the middle of 2008 the crisis was evident. There was a lot of square footage, much of it in the wrong places. There were issues with the supply chain for managing fresh and perishables, those very products that drive frequent footfall into a food store. More importantly, the global financial storm had started gathering strength, reducing liquidity in the market and making investors and lenders look more closely at existing business models.

The spectacular meltdown of Subhiksha in 2008, and the more gradual but equally deep impact on other businesses was visible. And worrying. Players as disparate as Reliance, with its ambitious plans to grow into a Rs. 300 billion retail juggernaut, and the Shopper’s Stop premium format Hypercity seem to take a break to rethink.

2008 and 2009 were years that I am sure many retailers would like to forget, but they were also very valuable. Some people have compared these years to the churning of the ocean (manthan) by the devas and the asuras in Indian mythology, with the deadly poison halahal coming to the surface before the divine nectar amrit could be reached.

In these two years, we have seen stores closed, formats changed, and organisations made slimmer. Store staff have discovered how to live with small changes like higher ambient air-conditioning temperatures, and are learning the more important science of higher transaction values, even with leaner inventories. Management teams are becoming more accustomed to looking at retail metrics other than only sales growth that could be achieved from new square footage. Vendors are finding newer ways to make their brands more relevant to consumers and to the retailers.

More importantly, these years have also underlined the importance of India as a growth market to non-Indian companies.

2010 so far seems a far happier year. Income and GDP growth figures look much healthier. Real estate inventories in malls that were not released in 2007-2009 are coming on the market, many at terms that are more favourable than earlier. Retailers’ financial results look healthier.

There could always be the temptation to rush headlong into growth again. But I don’t think food retailers or their vendors should drop their guard yet.

The coming months and years need significant sharpening up of customer insight, merchandise and inventory planning capabilities and supply chains. Operational assessments, analytics, organisational capability building, are all tools which will need to be looked at closely.

We are at the cusp of the next growth curve, as the population grows and matures, and the market become more sophisticated.

Though the large-small, local-foreign debate isn’t closed yet, the much-awaited approval from the government to allow foreign investment into multi-brand retail businesses may be around the corner.

Even if FDI doesn’t happen immediately, the majors are already in or preparing to enter and ride the consumption growth that will logically happen. In addition to its support to Bharti’s Easyday chain, Walmart has launched its cash and carry operation, Bestprice. Carrefour reportedly is looking to open its first Indian (wholesale) outlet by November in New Delhi on its own, even as rumours of a partnership with the Future Group fly thick and fast. And Tesco is steadily steaming ahead with the Tata group.

And practically every month we are seeing new products and even new brands being launched by Indian and non-Indian companies.

An old saying goes: the journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.

From the tumultuous events of the last three years, it seems that the Indian food retail sector must have travelled at least a few hundred miles already. In one sense it has. Many of the developments that we’ve seen in three years would have taken at least a couple of decades in the more mature markets.

However, in another sense, the food and grocery modern retail sector in India has only taken the first few steps, with much to be accomplished still. The sector remains fragmented, and wide swathes of the market are yet to be penetrated – not just by modern trade, but even by brands that already supply traditional retail. The blend of players and business models, not to forget the spicy regional mix of different market segments, promises valuable lessons not only for those in India but potentially for other markets in the world.

There are very big questions seeking answers. How to improve agricultural productivity so that food security is ensured. How to save the abundant harvests rather than letting them rot in unprotected storage dumps. How to ensure adequate calories and nutrition get delivered not just to the wealthy and the middle class, but also to the poorest in the country.

On the retail side, the Indian versions of Walmart, Carrefour and Tesco are possibly still in the making, and may yet surprise us with their origins and growth stories. And e-commerce is a work-in-progress that may be the dark horse, or forever the black sheep.

I think the big stories are yet to unfold, and the unfolding will be exciting, whether we are just watching or actively participating in the modernisation of the Indian food retail business.

Devangshu Dutta

February 19, 2009

Online retailer Zappos is planning to introduce customizable web pages, and that has attracted all kinds of commentary – warm & welcoming as well as dismissive.

The big question is “what is the customization and how it is being offered”.

My rule is simple: web-page customization has to drive simplification of the shopping experience.

Changing skins, page layout, and other cosmetic stuff may keep novelty-seekers happy – for some time, that is. But the average user will find that it is just another thing too many on the already over-full to-do list.

Simplification of the user-friendly sort has to be heuristics and analytics-driven, and behind-the-scenes. It has to be driven by not just stated preferences (through options / settings, through drag-and-drop etc.), but unstated – by studying past behaviour in both purchase and browsing. Imagine if you had every customer stating their preference for a physical store layout. In fact does everyone even know what they really want?

The flip side is that this kind of monitoring may sound creepy and 1984-ish to some people. But probably those would also be the people who are blissfully unaware of the fact that in today’s world the only way to remain totally untracked is to not use any form of electronic / communication device at all, or to build each such device (hardware AND software) yourself from scratch. If you use social networking sites, and have “friend suggestions” on your page, you are being tracked!

There is also the balance to be kept in mind between the boundaries the customer defines and promotions that the retailer wants to drive. The consumer may want to control completely what reaches her; the retailer may take the view that there are incredible deals which the consumer just wouldn’t know about if she built impregnable walls around herself.

For those who’re interested in customization, the British Broadcasting Corporation’s (BBC) document from 2002 about their 2001 website redesign (“The Glass Wall”) is a great resource to refer to. It doesn’t seem to be available anymore on the BBC website itself, but copies are available elsewhere on the web.