admin

January 15, 2026

Sagar Malviya, ET Bureau

Mumbai, 15 January 2026

It’s mostly a tale of two halves for top western fashion labels in India after the runaway sales and retail expansion in the years soon after the pandemic.

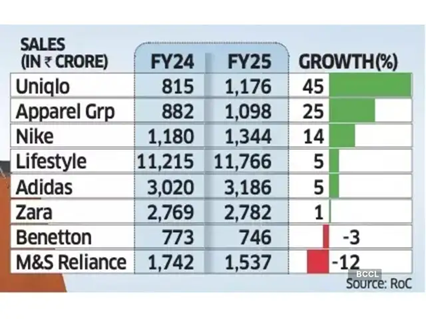

While Marks & Spencer, Benetton, and Adidas are battling waning demand, Uniqlo and Nike are gaining fresh ground, reflecting wider choices and increasingly discerning buyers in one of the world’s fastest-growing consumer economies.

Spanish brand Zara is facing stagnant growth while it tapered off at Apparel Group, which sells Aldo, and Charles & Keith brands in India. Experts termed the divergent sales performance as a potential structural shift instead of demand slowdown in India’s fashion and lifestyle market.

Devangshu Dutta, founder of retail consulting firm Third Eyesight, said consumers have clearly shifted towards function, even as trend-led brands continue to exist though they tend to be comparatively smaller. Some brands are also finding it harder to set or even follow trends the way they once did.

“This is especially true for Gen Z, which stays closely tuned to global trends and acts as the primary driver of fashion adoption,” said Dutta. “While older consumers may have greater spending power in absolute terms, it is younger shoppers who shape trends and influence product sales.”

Growth slowed across most leading retailers and fast-fashion brands in the country in FY24 as high inflation and stagnant incomes crimped discretionary spending.

While the trend remained the same for many even in FY25, select brands staged a strong rebound. For instance, Nike India’s sales rose 14% in FY25, up from a 4% increase in the previous year, while Uniqlo accelerated growth to 45%, from 31% in FY24.

Revival after Festive Season

Even Lifestyle, India’s biggest department store chain, grew 5% last fiscal, rebounding from a 4% decline in FY24.

Uniqlo said it continues to see steady momentum in India, supported by strong customer response, retail expansion, rising brand awareness, and a strong ecommerce uplift. “India is now among Uniqlo’s fastest-growing markets in Asia and plays a meaningful role in the region’s overall business,” Kenji Inoue, chief financial officer and chief operating officer, Uniqlo India told ET. “The country’s young demographic, growing focus on quality, and increasing appreciation for functional everyday clothing have all contributed to this progress.”

According to the Retailers Association of India (RAI), sales growth in organised retail segments such as apparel, footwear, beauty and quick service restaurants (QSR) saw single-digit sales growth last fiscal year but the market has recovered after the festive season with double-digit sales performance.

“Demand has improved, but it isn’t broad-based,” said Kumar Rajagopalan, chief executive at RAI which represents organised retailers. “With more fashion options available, Indian consumers are becoming more selective, and growth is coming to brands that offer a strong value proposition and not the cheapest products, but those where prices are justified by innovation, design and quality.”

In FY25, Apparel Group recorded a 25% sales growth, slowing from a 37% increase a year ago. Inditex Trent, which sells Zara in India, saw flat sales compared with an 8% growth in FY24.

Adidas too saw its revenue growth rate slowing to 5% from 20% in the previous fiscal. Sales of M&S and Benetton fell 12% and 3% each, respectively.

Being the world’s most populous nation, India is an attractive market for apparel brands, especially with youngsters increasingly embracing western-style clothing. However, most international and premium brands have been competing for a relatively narrow slice of the sales pie in large urban centres.

(Published in Economic Times)

admin

May 20, 2024

Sagar Malviya, Economic Times

Mumbai, 20 May 2024

Spain’s Inditex, the owner of fashion brand Zara, saw its slowest ever sales growth in India, excluding the pandemic year, in FY24 as the world’s largest fashion group faced rising competition from global rivals in the clothing market that is increasingly getting cluttered.

Inditex Trent, its joint venture with Tata that runs 23 of Zara stores in India, saw revenue rise 8% to Rs 2,775 crore last fiscal, significantly down from 40% growth a year ago, according to Trent’s annual report. Net profit was down too at Rs 244 crore, an 8% drop.

Zara has been a runaway success since its arrival in the country more than a decade ago but after initially doubling sales every two years, the brand’s rate of expansion had come down in the past few years. “The market is very competitive, and the challenges are real. Nevertheless, the opportunity pool and the size of the market means that there is space for multiple successful players. Trent remains well placed to navigate this next phase of growth by leveraging our platform and growth engines,” P Venkatesalu, chief executive officer at Trent, said in the report.

Trent that runs Westside has shifted focus on its lower priced fast fashion brand Zudio, which opened about four new stores every week on average last fiscal to take the total store count at 545 doors. Trent also has a separate association with the Inditex group to operate Massimo Dutti stores in India. The entity saw revenues rise 14% to Rs. 102 crore.

Experts said consumer demand has been affected in the past couple of years with brands having to work extra hard to get same-store growth and much of top-line growth has come for brands from store additions.

“Most international and premium Indian brands are competing for a relatively narrow slice of the population pie in the larger urban centres. While the Indian market is a bright spot amid the gloom in the world’s major economies, global pressures are likely to play a part in the confidence among brands to invest in expansion,” Devangshu Dutta, founder of retail consulting firm Third Eyesight, said, adding there is not necessarily “fatigue” for the brand.

“But if the contest for the consumer’s attention is more intense and the consumer’s choices are more fragmented across a wider choice of brands, that will definitely have an impact on any individual brand’s performance.”

Being the world’s second most-populous country, India is an attractive market for apparel brands, especially with youngsters increasingly embracing western-style clothing. Most of Zara’s back-end and merchandise sourcing are handled by Inditex, while the Tata expertise is mainly for identifying real estate and locations.

(Published in Economic Times)

admin

April 15, 2024

Sagar Malviya, Economic Times

Mumbai, 15 April 2024

Spanish fashion company Inditex said it will launch youth clothing brand Bershka and Zara Home in India this year.

“Bershka will open its first store in Mumbai Palladium, and Zara Home will open in Bangalore,” it said in its latest annual report.

Inditex had launched fast fashion brand Zara in 2010 and premium clothing brand Massimo Dutti eight years ago. Its new offering, Bershka, will pitch it directly against Reliance Retail’s Yousta, which too targets the younger consumer segment.

Being the world’s second most-populous country, India is an attractive market for apparel brands, especially with youngsters increasingly embracing Western-style clothing. Fast fashion brands such as Zara and H&M became runaway successes soon after they entered the country.

Experts said Bershka’s target consumer profile is mostly teens to mid-20s, slightly younger than that of Zara, which is pitched at 20-40-year-old fashion-driven customers.

“The product assortment is different, with a higher share of knits, fewer dresses and more casual overall compared to Zara, keeping in line with the lifestyles of the customer group. So in that sense it wouldn’t cannibalise Zara in any serious way, though some of the younger set among Zara buyers could migrate some of their purchases to Bershka,” said Devangshu Dutta, founder of retail consulting firm Third Eyesight. “The biggest question is, can they hit the price points that young Indian fashion consumers want as with domestic brands such as Zudio, Yousta and others, or will consumers overlook higher prices for the style mix and a European brand pull in significant numbers to make the brand viable.”

According to a recent report by Motilal Oswal, the ₹2.5 lakh crore value fashion segment accounts for 57% of the total apparel market and is one of the largest and fastest-growing segments. A substantial untapped opportunity beyond the metros and tier-1 cities, driven by better demographics, higher incomes and greater customer aspiration, has compelled several big players to enter a market that was previously dominated by regional and local operators.

Since its inception in 2016-17, Zudio has seen considerable expansion and reached nearly 400 standalone stores, outpacing most apparel brands primarily due to its competitively priced products with an average selling price of ₹300. Following the success of Zudio, a unit of the Tata Group’s Trent, the segment has seen the entry of national retailers in the affordable youth clothing segment such as Yousta by Reliance Retail, Style-Up by Aditya Birla Fashion and Retail and Shoppers Stop’s InTune.

(Published in Economic Times)

Devangshu Dutta

June 12, 2010

My first brush with Zara and Inditex (Zara’s parent company) was in the 1990s, when we were comparing product development and supply chain best practices for another European retailer.

In 2002, after writing a case study on the Zara business model, I was (and continue to be) surprised at the number of downloads from the website (referenced at the bottom of this article).

In 2004, the interest at the Images Fashion Forum was so intense that the Q&A after the presentation exceeded the allotted time, to the extent that I was almost declared persona non grata by the organising team!

I’m glad to say that we’re all still friends and, together, witness to the logical next phenomenon: the much anticipated Zara store launch in India in May 2010. And what a phenomenon! On a high-footfall day, at full price, the Delhi store looks as if the merchandise is being given away for free.

In 2006, India was the 8th highest source of traffic to the Inditex website (more than half a million, almost 2 per cent of the total); incredible, considering that the other Top-10 countries already had Inditex stores. Although Zara finally signed a joint-venture with the Tata Group, I’m pretty sure that those thousands of other rejected prospective Indian licensees and franchisees must be getting their Zara-fix now as customers.

What does the Zara launch mean for the Indian fashion and retail sector? Is this the beginning of a new era? Should we expect Zarafication of the market, where the customer is driven by fashion, and the supply chain will turn and churn products faster than ever before? Should other international brands and Indian fashion brands be worried?

A peek at history is useful here. It is said that when Spanish conquistadors landed on the shores of the Americas they managed to conquer the land and the people through a combination of guns, germs and steel. [Credits to Jared Diamond for that evocative phrase.] That is, the Spanish carried guns and fine steel swords but, most importantly, they also carried diseases that were alien to the local population. In many places, the weakened and leaderless indigenous people were simply too battered psychologically and physically by disease, to fight the colonisers.

Keeping that in mind I would say, Zara’s entry is a warning bell only if your business is suffering from recent financial and operational illnesses. It is only dangerous if your team are psychologically weak, and would be overwhelmed just by the thought of the supply chain wizardry that Zara has deployed in its business internationally. It may be fatal for sleepy marketing teams whose only strategy has been to spend lots of money on advertising in season and on mark-downs after the season.

But it’s not doom and gloom for brands and businesses that have a competitive spark of life. If you’re prepared to learn, Zara’s business can provide lessons on how to create a product mix that doesn’t stay on the shelf for months, and on how to create the buzz and excitement around the brand.

Zara’s business success in India is not a foregone conclusion. Let’s look at the facts.

Zara’s business model in its home market was built on getting up-to-date fashion into the market before anyone else, and at lower costs. Its prices encouraged fashion-conscious consumers to buy more frequently, and though its limited production quantities were a way of reducing risk, it added to the allure of the brand. In most overseas markets, however, Zara is a somewhat more premium brand. The “value-for-money” for the brand rests on fashionability rather than product quality.

The Indian consumer base, on the other hand, is less fashion-sensitive than the European consumer. This is not equivalent to being less sensitive aesthetically – Indian consumers can tell good design from bad; allowing, of course, for varying taste! However, value consciousness drives many consumers to buy during discount sales with delay of 2-3 months, rather than buying current fashions at full price. This can be a problem for a brand that thrives on change.

Zara will initially have a limited physical footprint. It is targeted at the premium to luxury end of the market, fitting a certain physical profile of customer. Its products that are imported are disadvantaged by a hefty import duty and shipping costs, as well as the shipment lead time. So, there is time available to Indian businesses that want to adapt their business model, and learn from this new competitor.

With the product development strengths and the agility that Indian apparel companies have displayed in the past, there is no reason why Indian brands cannot compete effectively with Zara on their home turf. When it comes down to it, I think Indian businesses (the small ones, with less “organisation” and “process” orientation) are fast on their feet in identifying design trends and are able to responding to the trends with products being available in the market very quickly. I would call them the Indian “baby Zaras”.

So the real question is this: can these Indian “baby Zaras” learn to be disciplined and structured, and learn to scale up their businesses?

Could we, perhaps, even see some people creating copies of Zara’s styles and bringing them to the market quickly at much lower prices (in effect doing a Zara on Zara)? Let’s not forget, what is today an 11-billion Euro business was once a contract manufacturer to other retailers, and Zara started with one shop carrying low-priced versions of products inspired by those of high-fashion designer brands.

The coming years promise to be interesting and I think we should watch out for an Indian version of an Inditex emerging in the next few years. It remains to be seen whether it will be from among the existing players in the domestic market, an exporter who is a contract manufacturer for western retailers (as Inditex once was), or someone totally new.

The people who should be really worried are those international brands whose product mix in India is weak, whose prices make you want to marry a rich banker, and whose brand ethos is totally unclear. To them I would say: Zara has you in its gun-sights.

Devangshu Dutta

May 11, 2010

REVIEW: BEATING THE COMMODITY TRAP: Richard D’Aveni (Harvard Business Press)

In his latest book, Professor Richard A. D’Aveni focusses on a topic that most businesses should be acutely concerned with: the problem of commoditization. In interviews he has accurately described commoditization as “the black plague on modern corporations” and “a deadly disease that’s spreading like crazy”.

Certainly, if one had to pick the ultimate nightmares to keep CEOs awake at night, commoditization would definitely be among the top of the list. Specifically, given the economic uncertainties around the world in the last couple of years, business leaders who are not concerned about their products or services being turned into commodities are either supremely equipped to maintain their differentiation, or immensely deluded as to their capabilities to fight market forces. Prof. D’Aveni suggests that maintaining differentiation alone is not enough to sustain business.

A product or service becomes a commodity when it is not distinguishable from competing offerings and therefore not valued above the competition. Prof. D’Aveni views commoditization along two key attributes: the benefits or features that are being offered and the price (margin) that is available to the business. Based on his model, he has identified three types of competitive stress that a business could face:

The book suggests competitive strategies that a business could take to avoid getting caught in the commodity trap. These strategies can be boiled down to the biological choice: fight or flight (escape). Professor D’Aveni echoes the basic warfare strategy laid out by many military and business strategists through the ages. He suggests that businesses need to gauge the opponents, choose their battles, and pick opponents against whom they can win. He also calls for pre-emptive action: where companies can, they should either change the business environment to avoid commodity battles entirely, or initiate the battle of commoditization and control its direction and momentum.

In fact, anticipation and pre-emption is the key to avoiding the commodity trap. To help with this, Prof. D’Aveni offers a relatively simple framework to analyse a current market situation in terms of a price-benefit matrix, and to identify the advance corrective actions to be taken.

The book is short and straight-forward enough to pick through a domestic flight, or to read in the back-seat during a long commute between office and home. The easy to understand framework gets the messages across quickly. In analysing the variations of commoditization, both in consumer and business oriented industries, the Professor also offers up something for everyone.

However, the book’s strengths also turn out to be among its biggest weaknesses. The book would have benefited from more depth to each of the concepts. Skipping quickly from one area to the other, in some places the book risks losing coherence of thought.

Some short books are like downhill hairpin bends on a mountain road; Prof. D’Aveni’s book is one of those. Much as you might be tempted to go fast, it’s advisable to go slow. If you speed through it, you might miss a nugget that actually makes sense to your business.

One of the other grouses I had was with the examples quoted. The predominantly US market examples reduce the book’s relevance for a global audience – the Professor presumes the reader will know the company and its context well enough to understand the lessons being discussed. In some cases the examples are incomplete and possibly even incorrect: one such is the example of Zara. The broad-brush attributes Zara’s business success to turning fashion into commodity, and ignores the fact that fashionability and desirability are a cornerstone of Zara’s offer, not the cheapest price. Others would possibly be far more accurate examples of commoditization in the context of price.

However, if you are sufficiently concerned about the possibility of being commoditized out of profitability, or being marginalised out of market share, I would suggest that you could easily overlook these flaws. The fundamental premise of the book is far too important to ignore. [Beating the Commodity Trap on Amazon]

(This review was written for Businessworld.)