admin

January 15, 2026

Sagar Malviya, ET Bureau

Mumbai, 15 January 2026

It’s mostly a tale of two halves for top western fashion labels in India after the runaway sales and retail expansion in the years soon after the pandemic.

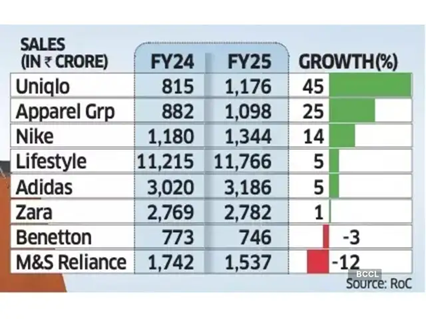

While Marks & Spencer, Benetton, and Adidas are battling waning demand, Uniqlo and Nike are gaining fresh ground, reflecting wider choices and increasingly discerning buyers in one of the world’s fastest-growing consumer economies.

Spanish brand Zara is facing stagnant growth while it tapered off at Apparel Group, which sells Aldo, and Charles & Keith brands in India. Experts termed the divergent sales performance as a potential structural shift instead of demand slowdown in India’s fashion and lifestyle market.

Devangshu Dutta, founder of retail consulting firm Third Eyesight, said consumers have clearly shifted towards function, even as trend-led brands continue to exist though they tend to be comparatively smaller. Some brands are also finding it harder to set or even follow trends the way they once did.

“This is especially true for Gen Z, which stays closely tuned to global trends and acts as the primary driver of fashion adoption,” said Dutta. “While older consumers may have greater spending power in absolute terms, it is younger shoppers who shape trends and influence product sales.”

Growth slowed across most leading retailers and fast-fashion brands in the country in FY24 as high inflation and stagnant incomes crimped discretionary spending.

While the trend remained the same for many even in FY25, select brands staged a strong rebound. For instance, Nike India’s sales rose 14% in FY25, up from a 4% increase in the previous year, while Uniqlo accelerated growth to 45%, from 31% in FY24.

Revival after Festive Season

Even Lifestyle, India’s biggest department store chain, grew 5% last fiscal, rebounding from a 4% decline in FY24.

Uniqlo said it continues to see steady momentum in India, supported by strong customer response, retail expansion, rising brand awareness, and a strong ecommerce uplift. “India is now among Uniqlo’s fastest-growing markets in Asia and plays a meaningful role in the region’s overall business,” Kenji Inoue, chief financial officer and chief operating officer, Uniqlo India told ET. “The country’s young demographic, growing focus on quality, and increasing appreciation for functional everyday clothing have all contributed to this progress.”

According to the Retailers Association of India (RAI), sales growth in organised retail segments such as apparel, footwear, beauty and quick service restaurants (QSR) saw single-digit sales growth last fiscal year but the market has recovered after the festive season with double-digit sales performance.

“Demand has improved, but it isn’t broad-based,” said Kumar Rajagopalan, chief executive at RAI which represents organised retailers. “With more fashion options available, Indian consumers are becoming more selective, and growth is coming to brands that offer a strong value proposition and not the cheapest products, but those where prices are justified by innovation, design and quality.”

In FY25, Apparel Group recorded a 25% sales growth, slowing from a 37% increase a year ago. Inditex Trent, which sells Zara in India, saw flat sales compared with an 8% growth in FY24.

Adidas too saw its revenue growth rate slowing to 5% from 20% in the previous fiscal. Sales of M&S and Benetton fell 12% and 3% each, respectively.

Being the world’s most populous nation, India is an attractive market for apparel brands, especially with youngsters increasingly embracing western-style clothing. However, most international and premium brands have been competing for a relatively narrow slice of the sales pie in large urban centres.

(Published in Economic Times)

admin

September 24, 2025

Shabori Das & Sagar Malviya, Economic Times

Bengaluru/Mumbai, 24 September 2025

Chinese fast-fashion platform Shein plans to triple the number of launches in India and shrink its design-to-launch timeline by a third to deepen its push into an increasingly competitive market, a top official said.

The company, which re-entered India through a partnership with Reliance Retail in February this year, said it is overhauling its supply chain to enable faster turnaround times. To achieve this, it has moved away from large-scale manufacturing hubs to smaller production lines with each line focused on creating a single new design daily.

“Our current timelines, measured from ‘thought to site’, stand at 46 days. We are targeting 30 days,” said Vineeth Nair, chief executive of Reliance’s fashion platform Ajio that steers Shein in India. “We currently deliver 320 styles a day – about 10,000 a month – and plan to scale that to over 30,000 styles monthly in the coming months,” he told ET.

Speaking about the speed of manufacturing, Nair said, “We quantify our options in terms of production lines, with each line optimised to deliver one design option per day, rather than factories. Some of our large production units have been repurposed into multiple lines.”

Shein first launched in India in 2018 with its own online shop. However, the app was banned by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) along with TikTok, WeChat and over 55 other Chinese apps.

One of the primary issues and controversies surrounding Shein’s India operations was the use of the consumer data by the Chinese apparel retailer.

Under the current partnership model, Reliance Retail is operating Shein under licensing agreement and ensures complete customer data ownership as per the company.

Unlike international markets, Shein India products are made in India.

“It’s still early days – just about three months since we introduced Shein to the India Gen Z,” Nair said. “And we are still in the process of adding multiple products, which we intend to do in the next few months.”

He said the brand is witnessing two million daily average users, dominated by 21-year-old women who account for 62% of the traffic.

Shein, the world’s biggest ecommerce-centred fashion retailer, however, may find it hard to replicate its global success in India, according to Devangshu Dutta, founder of retail consulting firm Third Eyesight.

“Shein’s edge internationally has been its speed of dropping its products, and the width of its product category. The India model is not the same. The India model of fashion is slower, and the product category width is not as large,” he noted. “Hence, the brand will in all probability end up competing with the already established market like Myntra, Zudio and the likes.”

(Published in Economic Times)

admin

May 23, 2025

By Kunal Purohit and Ananya Bhattacharya, Rest of World

Mumbai, India, 23 May 2025

Online retail continues to elude India’s richest man.

The Shein India app, launched by Mukesh Ambani’s Reliance Retail in partnership with the Chinese fast-fashion giant, has struggled to gain traction in a market where Amazon and Walmart have been fighting neck-to-neck for nearly a decade. Downloads for Shein India nosedived from 50,000 a day shortly after its launch in early February to 3,311 in early April, according to AppMagic, a U.S.-based app performance tracker.

In April, when U.S. tariffs hit China, the app saw renewed interest as it was in the news, but experts are unclear on whether this growth is sustainable.

“Unlike earlier times, now … [the] market is saturated with multiple options and offers, and user interest can quickly dwindle,” Yugal Joshi, partner at global research firm Everest Group, told Rest of World.

Kushal Bhatnagar of Indian consulting firm Redseer, however, sees the late-April spike as a healthy sign, given that Reliance has yet to run paid marketing campaigns for Shein.

Reliance Retail declined to respond to Rest of World’s queries about its partnership with Shein.

Reliance launched Shein for India five years after the original Shein app was banned in the country over border tensions with China. But the Shein that has returned is entirely separate from Shein’s global platform: Rather than selling made-in-China clothes and accessories directly to consumers, Shein now operates as a technology partner, while Reliance Retail handles the heavy lifting — from sourcing and manufacturing to distribution. All consumer data is managed by the Indian company.

The partnership is part of Ambani’s broader effort to overhaul his retail business, whose valuation fell to $50 billion in 2025 from $125 billion in 2022. Although the company has made a push into digital platforms like JioMart, Ajio, and most recently Shein India, the bulk of its retail revenue still comes from its 18,000 physical stores.

Lagging behind Amazon and Walmart-backed Flipkart, which together control nearly 60% of India’s e-commerce market, Reliance has spent years trying to break into the sector. Between 2020 and 2025, Ambani’s group acquired majority stakes in companies spanning digital services, online pharmaceuticals, and quick commerce. But the investments have yet to position Reliance as a serious challenger to Amazon and Flipkart.

Analysts say the Indian behemoth hopes to leverage Shein’s artificial intelligence-powered trendspotting and automated inventory systems to pursue an ambitious goal: capturing a major share of India’s e-commerce market, projected to hit $345 billion by 2030.

According to Kaustav Sengupta, director of insights at VisionNxt, an Indian government-funded initiative that uses AI to forecast fashion trends, such a model is likely to make good use of Reliance’s humongous customer data sets: more than 476 million subscribers for its Jio telecom brand, 300 million users for e-commerce platform JioMart, and 452 million subscribers for its news and entertainment portfolio, consisting of 63 channels, a streaming service, and digital news outlets.

“With these data points, Reliance wants to now sell fashion products, so all it needs is a system where it can feed all these data points,” Sengupta told Rest of World. He said the model would be able to predict best-selling products and suggest the right prices for them.

The original Shein app uses AI-driven models for intelligent warehousing and to spot customer trends before manufacturing a new product. It scales the manufacturing up or tweaks the designs based on the feedback. At any given time, the Shein website has a catalogue of more than 600,000 items. Its Indian iteration does not match up, according to reviews on the Google Play store. Several customer reviews for Reliance’s Shein app are critical of higher prices and reduced options. The app’s rating hovered at 2 out of 5 until February; in May, it climbed to 4.4, but reviews were still a mixed bag.

Reviews of the Indian app highlight the disparity with Shein’s global version, criticizing higher prices and a reduced selection of categories and styles.

As of April 25, Reliance Retail said only 12,000 products were live on Shein India, a stark contrast to the 600,000 items available on Shein’s global platforms. While Shein is reportedly set to debut on the London Stock Exchange this year, Ambani’s years-old promise to take Reliance Retail public remains unfulfilled.

Reliance Retail, which accounts for around 30% of the conglomerate’s overall business, is facing a slowdown in annual growth. Its sales rose just 7.9% in the fiscal year ending March 2025, down from 17.8% the previous year. Meanwhile, shares of rival Tata Group’s retail and fashion arm, Trent, have soared by 133%.

“Reliance would have looked at reviving that momentum and riding on it, while for Shein, adding India back on its portfolio of markets could be a plus point before its proposed public listing,” Devangshu Dutta, founder of Third Eyesight, a brand management consultancy that has worked with various global e-commerce brands including Ikea, told Rest of World.

A Reliance Retail official privy to information about its fast fashion expansion plans told Rest of World the partnership with Shein also hinges on global manufacturing ambitions as the Chinese company is trying to “source its products from other countries like India” to meet the “additional demand that is coming from newer markets.” Reliance Retail has tapped a network of small and midsize Indian manufacturers to locally source products, and its subsidiary Nextgen Fast Fashion Limited is leading the charge. “We need to first scale up our domestic manufacturing, before our partnership starts manufacturing for global markets. Let us see how that goes, first,” the official said, requesting anonymity as he is not authorized to share this information publicly.

India’s Gen Z population is at 377 million and counting, and their spending power is set to surpass $2 trillion by 2035, according to a 2024 report by Boston Consulting Group. Every fast-fashion retailer wants to capture this market, but it “is very new even for Reliance,” Rimjim Deka, founder of Indian fast-fashion platform Littlebox, told Rest of World.

Deka said smaller brands like hers “just see [a trend] and implement it,” which could take a large conglomerate months to do, by which time the trend may have lost relevance.

Reliance’s previous attempts to attract young shoppers with clothing brands like Foundry and Yousta failed to find much success. Anandita Bhuyan, who works in trend forecasting and product creation for fast-fashion clients like H&M and Myntra, told Rest of World the company has struggled to effectively leverage consumer data and target India’s youth.

According to the Reliance Retail official, the company is confident that if “there are 10 existing brands, the 11th brand will also get picked up as long as there is value and there is fashion.”

“Shein already has a recall among the youth. It gives us yet another brand in our portfolio through which we can cater to the youth,” the official said.

Shein was built in China on the back of more than 5,400 micro manufacturers — a scattered and loosely organized network of small and midsize factories.

In January this year, on a visit to China, Deka met with manufacturers working for Shein and Temu. On the outskirts of Guangzhou, Deka saw factories set up in areas that appeared residential, with “women sitting inside houses” making clothes.

“The tech is built in a way that somebody sitting there is able to see that, okay, next 15 days or next one month, how much I should be making … that is the kind of integration they have done,” Deka said.

Deka told Rest of World this model is easier to replicate at a smaller scale. “Me, coming from [the] supply chain industry, I understand that it is much easier for a brand like us because we are at a very smaller scale. We can still go to those people, we can still build it in a very unorganized way and then pull it off,” she said. Her company’s annual net revenue is 750 million Indian rupees ($8.6 million).

“[But] somebody like Reliance, they just cannot go haphazard here. … It has to be always organized,” Deka said.

Shein moved its headquarters to Singapore sometime between late 2021 and early 2022, a strategic departure to distance itself from its Chinese origins and facilitate hassle-free international expansion amid the U.S.-China trade war.

India is part of Shein’s wider strategy to diversify its supply chain — one that also includes a newly leased warehouse near Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam, and efforts to establish alternative manufacturing hubs in Brazil and Turkey.

But in India, Reliance needs Shein as much as Shein needs Reliance for its global pivot. According to Bloomberg, Reliance Retail is focusing on creating leaner operations to weather a wider consumption slump in the Indian economy.

“It remains to be seen whether the Reliance-Shein combine can deliver on the brand’s promise with a wide range of products, fast and on-trend,” Dutta said. “In the years that Shein has been absent, the Indian market has evolved further, competition has intensified, and past goodwill is not enough to provide sales momentum.”

Kunal Purohit is a freelance journalist based in Mumbai, India.

Ananya Bhattacharya is a reporter for Rest of World covering South Asia’s tech scene. She is based in Mumbai, India.

(Published in Rest of World)

admin

February 23, 2025

Chitra Narayanan, BusinessLine

New Delhi, 23 February 2025

India’s formidable array of craft traditions got full play at the just concluded Bharat Tex 2025, the mega textile trade show in New Delhi that showcased the best of Indian weaves to the world. But if there was one theme that dominated this year’s textile extravaganza, aimed at generating more exports, it was the focus on zero-waste fashions and upcycling. Everywhere the eye could see were standees and gigantic posters pushing the message of conscious consumption and sustainability — be it regenerative cotton, innovative models of textile waste collection, or eco-friendly fibres.

Taking centre stage at one of the halls at Bharat Mandapam, the venue, was a section that showcased age-old traditional arts like rafugari (creative darning or artistic mending), patchwork quilts and toys, and chindi durries (the art of weaving rugs and carpets with waste).

Juxtaposed against these ethnic ways of upcycling waste were the modern works of startups that rose to the textile ministry’s grand innovation challenge to work with discarded materials. From microbial dyes that are non-polluting to flowing fashionable lehengas created out of textile waste, the startups showed that a lot can be done in this area. The ministry had challenges in three more segments — jute, silk and wool.

Some takeaways from a walk-through of the textile trade show:

Closing the loop

The fashion and textile industry generates enormous waste. How to cut down on this was a subject of much deliberation and showcases. There were a lot of good ideas on display, showing that a fair amount of work has been done with fibres (bamboo, banana, flax), as well as creativity and ingenuity in weaves and finished garments.

As Devangshu Dutta, Chief Executive of the consultancy Third Eyesight, points out, due credit must be given for the good work going into generating solutions that will reduce waste, be it textiles that are reprocessed and reused as yarn, or refashioned garments or reloved apparel. But, as he adds, on the other hand we have brands that are constantly looking to grow their business and there is a race to the bottom in terms of price. The relaunch of fast fashion retailer Shein in India is sending conflicting signals. “The basic engine is pumping out more and more products, and that has to be tackled,” he says, pointing to the competing forces at work.

The source of hope, he says, is the fact that the young are a bit more conservative about how they consume and what they consume.

Sandip Ghose, CEO of MP Birla Group, which has one of the oldest jute companies in India, was among the visitors at Bharat Tex. “As an industry insider, what I found good at Bharat Tex was that quite a bit of research seems to be on, both for finished fabric and for weaving. There was a lot of work on making jute look aesthetic. There were some vanity projects like tea leaves packed in jute bags. But the challenge is in two areas — commercialisation, and scaling up of these ideas,” he says.

He rues that the jute sector has not taken advantage of the production-linked incentive scheme at a time when the world is looking for eco-friendly and biodegradable textiles. “A tripartite partnership between the Centre (Niti Aayog and textile ministry), State government, and industry would address the issue of industry’s dependence on subsidies, labour issues and exports,” he says, adding that if India is looking at textiles as a major export area, jute is an option that has been missed.

Spinning into luxury

A clear trend evident from a tour of some of the apparel and home textile pavilions is the move towards premiumisation, similar to what is visible in other sectors, noticeably FMCG.

Talking to the manufacturers, especially those focused on the domestic market, the story one heard was that consumption had slowed in the mass segment, but was reassuringly strong in the premium segment.

Several players were also moving into the luxury and uber luxury segments. Both myTrident and Welspun had striking luxury collections.

Another trend visible in the home textiles section was the use of celebrity designers — myTrident’s eye-catching collection by resort-wear designers Shivan-Narresh; and Welspun’s beautiful sets from Kate Shand and Payal Singhal.

“When the economy suffers, it is the poor and middle class who cut down. There is no pressure to reduce consumption at the upper levels, and companies will try to tap into demand that is recession-proof,” says Dutta, explaining the push towards luxury by textile manufacturers.

New trade routes?

Export houses seemed reasonably happy with the buyer interest. Some mentioned that it was interesting to see buyers from Russia at the fair. However, for those supplying to US entities and Western Europe, the buyer interest from Russia may not translate into deals, given the risk of sanctions they could face.

To sum up, it was a fairly good showcase of India’s textile prowess to the world, but whether it will ring in more export orders is debatable as many of the problems and challenges the sector faces were swept under the carpet.

(Published in BusinessLine)

Devangshu Dutta

December 24, 2024

Opinion piece by Devangshu Dutta, published in TexFash.com

12 December 2024

TLDR:

The core premise of quick commerce is time-sensitive buying by the consumer, typically emergency purchases and top-ups of food and grocery, cleaning or personal care items. Although 10-minute delivery has been widely hyped, deliveries are usually—and more realistically—made in a time span of 20–60 minutes, which is often better than the cost and time involved in driving to nearby stores that are beyond walkable distance, in India’s crowded urban environment.

While quick commerce platforms had already begun disrupting FMCG and grocery buying, impacting traditional kirana shops, recently they have also started adding fashion products to improve their margin mix and profitability.

The fashion business, by its very nature, is built on width of choice, frequency of change and unpredictability, whereas the quick commerce business model depends on a narrow, shallow merchandise mix which comprises products that are sold predictably, frequently and in large numbers within a small delivery radius. Stocking a variety of fashion styles, sizes, and colours is inherently more complex than handling products like soaps or spices.

Also, unlike FMCG or essential products, fashion items certainly depend on sensory experience of touch and feel. Shopping for clothing often requires browsing through a variety of styles, fabrics, and fits; consumers spend considerable time researching, comparing, and reading reviews to ensure the right fit, colour, and fabric.

However, there is potential for basics (e.g. T-shirts in common colours, innerwear, socks, and hosiery), last-minute outfit changes, urgent replacement for damaged clothing, event-driven products, or specially promoted products that look like great deals, as all of these would fulfil immediate needs without the same level of evaluation and comparison.

In contrast, fashion shopping for high-value items such as dresses, shirts, or outerwear will remain a slower, more deliberate process. The higher the emotional or experiential value attached to a product, the less quick commerce will fit.

Myntra has announced its quick commerce launch offering 10,000 styles, across fashion, beauty, accessories and home, and expects to expand the offering to over 100,000 products in 3–4 months.

I see Myntra’s entry into this space partly as a defensive move to fend off the quick commerce upstarts from cannibalising its business in a market that is already beset with damp offtake and highly discounted sales. Surely Myntra would not want to lose its customers who may looking to make repeat, impulse or emergency purchases of fashion products and may be less price sensitive while doing so.

It’ll be interesting to see how they address the product complexity with super-quick deliveries, and how geographically spread this business model can be for Myntra.

Myntra’s parent company Flipkart has already announced that it expects to IPO by 2025–26, and it needs to be seen as evolving and staying relevant in an increasingly competitive environment, rather than losing customers and business to younger q-commerce businesses.

We shouldn’t confuse quick commerce with “fast fashion”. What is fast in quick commerce is the speed of decision making and shopping that is enabled by a limited choice, and fast deliveries.

The fast fashion model is built on the foundation of changing trends, which needs companies to quickly identify winning trends, get product ready to sell, and move out of trend so as not to be stuck with out-of-demand inventory. The fashion-conscious customer profile wants frequent and, most importantly, trendy changes to their wardrobe. Fast fashion is waste-inducing because it encourages discarding products that are out of trend, but otherwise perfectly fine.

Quick commerce, on the other hand, needs to have a profitable business on a much narrower product profile. The more predictable and basic the product, the more it suits a Q-commerce business model.

Sustaining the ability to make fashion-trend related changes to the product mix would be nightmarishly complex for quick commerce.

I would expect quick commerce of fashion to be more driven by “need” than by “want”, and in that aspect to be, hopefully, less waste-inducing and perhaps less environmentally harmful than the established fast fashion business models and brands.

Quick commerce could also create an additional outlet for inventory that is stuck and feed into value-conscious customers’ requirements.

For small manufacturers, Myntra’s entry into the q-commerce space could be a double-edged sword.

On one hand, quick commerce can create a new demand channel for them beyond modern retail, traditional stores and online marketplaces, offering growth in a tough market environment.

However, it can also intensify the pressure on their already tight margins because of the consolidation of trade demand and a push by large customers such as Myntra to improve their own profitability. Suppliers may also be asked to hold inventory at their end ready for replenishment of the quick commerce dark stores, to ensure that service levels are maintained.

This can increase pressure on production timelines and on working capital for small manufacturers, who would need to adapt quickly or risk being squeezed out by larger, more agile competitors.

On the competitive side, while larger retailers—whether traditional, family-owned department stores or large chains—are likely to be less affected, quick commerce of fashion products will certainly hit smaller fashion stores whose merchandise mix is limited in width and depth. These stores will necessarily need to define what is their continuing value proposition to the changing consumer.